08 Jul Jesse Jackson Is Taking on Silicon Valley’s Epic Diversity Problem

IN MAY 2014, the Reverend Jesse Jackson traveled from his home in Chicago to the Googleplex in Mountain View, California, to address the search giant’s annual shareholder meeting. Technology isn’t what you would call a core area for the 73-year-old civil rights leader, who carries an old-school flip phone and oversees a website, Rainbowpush.org, that looks like a relic from the GeoCities era. But Jackson had a bone to pick. Despite Google’s mission to make the world’s data “universally accessible and useful,” it had been fighting for years to stop the release of federal data on diversity in its workforce. “There should be nothing to hide, and much to be proud of and promote,” Jackson told the company’s executives after politely requesting its diversity stats. “I ask you, in the name of all you represent, to pursue this mission.”

David Drummond, the company’s only black high-level executive, sized up Jackson, who stood out amid the mostly white crowd. “Many of the companies in the Valley have been reluctant to divulge that data, including Google,” he responded. “And quite frankly, I think we’ve come to the conclusion that we’re wrong about that.”

The exchange was the public culmination of some behind-the-scenes arm wrestling that was vintage Jesse Jackson. Drummond, 52, was an old friend of the reverend who had volunteered for his 1988 presidential campaign and helped launch Jackson’s first tech initiative, the Silicon Valley Project, 11 years later. The two men had met quietly a month or so earlier at Google HQ, and again around the time of the shareholder meeting. Drummond knew Jackson would ask for the stats, and Jackson knew Drummond would agree to release them. Two weeks later, Google’s senior vice president of people operations, Laszlo Bock, did just that. “Put simply, Google is not where we want to be when it comes to diversity,” he said, upon revealing that the company’s overall workforce was only 30 percent female, 3 percent Hispanic, and 2 percent black.

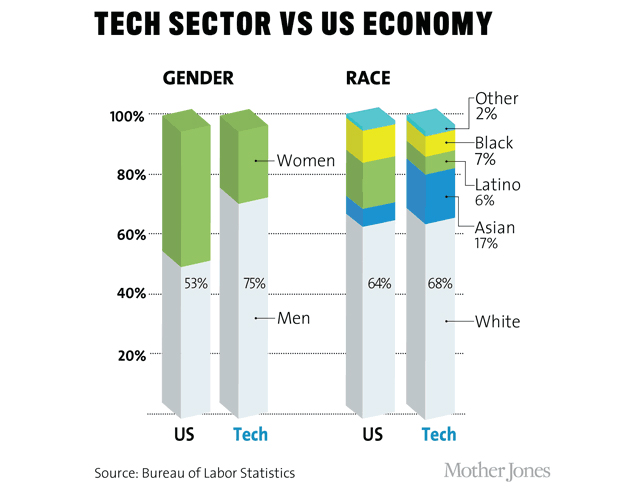

Rather than simply criticize Google’s abysmal numbers, Jackson issued a statement calling for other companies to “follow Google’s lead” and release their data too. Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Amazon, and Apple did so a few months after, and it wasn’t pretty: In most cases, less than 10 percent of the companies’ overall employees were black or Latino, compared with 27 percent in the American workforce as a whole. This chart reflects the broader tech sector:

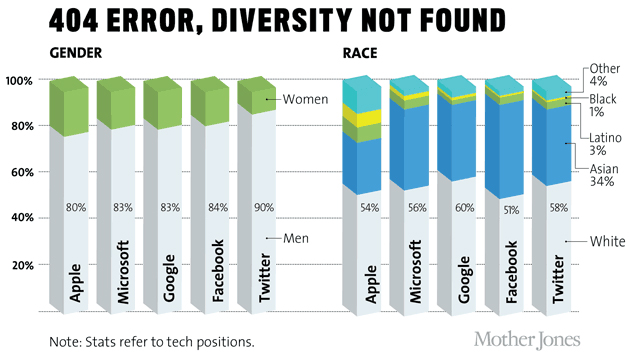

The technical workforce is even more homogeneous. Take Facebook, whose just-updated numbers show that it’s tech employees are just 16 percent female, 3 percent Latino, and 1 percent black. It’s worse at the top: Whites hold nearly three-quarters of Facebook’s senior leadership positions. Facebook is hardly alone. By the accounting of Jackson’s advocacy organization, the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, the 189 board directors at 20 leading tech companies included only 36 women, three blacks, and one Latino.

Diversity has been “completely off the radar screen” in Silicon Valley, Jackson tells me one January afternoon. Clad in a charcoal-colored suit and violet dress shirt, he’s sitting in the passenger seat of my rented Ford Focus as I navigate Palo Alto traffic en route to his next speaking engagement. His knees bump up against the dash. A former college quarterback from Greenville, South Carolina, Jackson stands 6-foot-2 and retains that fiery charisma from his days as a rabble-rouser—though age seems to have tempered him a little. Butch Wing, his right-hand man on tech issues, chimes in occasionally from the backseat with a date or the proper name of a CEO, but Jackson, who studied to be a Baptist minister before going to work as an organizer for Martin Luther King Jr., is more concerned with the big picture. “We have been pre-occupied with getting free from slavery, free from Jim Crow, free to vote,” he says. “So we are free, but unequal. And the equality side of the equation is where there have not been vigorous fights.”

Jackson, who has a history of pressuring companies on race and labor issues, has recently, perhaps improbably, emerged as something of a Silicon Valley power player. In March 2014, his Rainbow PUSH Coalition opened an office in the Bay Area. Since then, Jackson has been popping up seemingly everywhere, from a protest held by security guards at the Apple campus to a seat near Intel CEO Brian Krzanich at Las Vegas’ massive International Consumer Electronics Show. His PUSHTech2020 Summit, held in San Francisco this past May, featured prominent tech entrepreneurs, a $10,000 contest for minorityowned startups, and a fancy dinner reception at Yelp headquarters.

In a tech world that often defines ancient history as what happened last year, Jackson offers a dose of perspective, highlighting a legacy of racism beneath the Valley’s egalitarian self-image. His message is resonating—or at least freaking people out. In the past year, he has helped prompt unprecedented disclosures, mea culpas, and financial commitments from a who’s who of technology companies.

How much credit he deserves for these changes depends on whom you ask. “They say that where there’s smoke there’s fire,” says Freada Kapor Klein, cofounder of the Oakland-based Kapor Center for Social Impact, which promotes race and gender diversity in technology. “Jesse Jackson is the smoke. If he’s blowing in, I guess it means the rest of us are doing something right.”

Then again, not every activist can land a meeting with Tim Cook or Satya Nadella simply by picking up the phone. Jackson “just gets into rooms,” says Laura Weidman Powers, the cofounder of Code 2040, a leading incubator of minority tech talent. “And people listen.”

Intel execs, who’ve met with Jackson several times over the past year, credit him with helping inspire the company to pledge an unprecedented $300 million to make its workforce more diverse. Apple, after a series of private meetings with Jackson, agreed to donate $40 million to the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, which bankrolls scholarships and programs at historically black colleges and universities. And Google has dispatched its own engineers to some of the schools to teach introductory computer science courses and help graduating students prep for their job searches.

“A huge amount of credit for the conversation about diversity and technology ultimately has to go to Jesse Jackson,” says Van Jones, cofounder of #YesWeCode, a movement to train low-income teens as programmers. “You can’t solve a problem you can’t measure, and a lot of tech companies have [waged legal fights] to prevent themselves from having to release their data. Jackson was able to convince them to become transparent, and that is why you suddenly now see this whole flourishing set of initiatives.”

Jackson has a long track record of getting his way as a negotiator. He has successfully bargained for the release of US soldiers, journalists, and civilian hostages held by Fidel Castro, Saddam Hussein, Slobodan Milosevic, and others. But not everyone appreciates his tactics. “Jackson’s true métier is the business shakedown,” conservative commentator Carl Horowitz wrote last year on the site Townhall after Jackson spoke at the shareholder meetings of Google, eBay, and Facebook. Horowitz accused Jackson of using a blend of “charisma and menace” to pressure corporations into discriminating against white applicants and giving money to Rainbow PUSH.

Yet this critique fails to account for Jackson’s personal appeal. This past December, during a visit to Intel’s Santa Clara headquarters, he was mobbed by selfie-snapping employees, whom he gathered into an impromptu circle to chat about his work. “They were all captivated,” recalls Rosalind Hudnell, Intel’s chief diversity officer. Jackson, after all, is “one of the leaders that’s tied to a significant transformation in this country’s history. And that brings a lot of value to what we are doing.”

IN SOME WAYS, Jackson’s work in Silicon Valley represents a return to his roots. Back in 1967, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference tapped him to lead Operation Breadbasket, an effort to use boycotts to pressure white-owned businesses to hire more African Americans and purchase more goods and services from black contractors. Jackson would later use similar methods to push for diversity concessions from the likes of Anheuser-Busch, CBS affiliates, Coca-Cola, Ford, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Toyota, and Texaco, which agreed to settle a discrimination lawsuit for $176 million soon after Jackson targeted it with a boycott.

Around the same time, though, a powerful conservative backlash was emerging. As a 1996 presidential candidate, Sen. Bob Dole spread fears about race-based “preferences” and “quotas.” California’s Proposition 209, enacted by voters that year, barred state institutions from considering race in hiring or college admissions. From 1995 to 1998, the proportion of whites who felt that blacks “have as good a chance as whites” to get “any type of job for which they are qualified” jumped from 68 percent to 82 percent. Many were convinced the country had become colorblind, and the election of Barack Obama in 2008 only reinforced that view.

Blacks did, in fact, gain economic ground relative to whites throughout the 1990s, but the gap widened again, and dramatically so, during the Great Recession. By 2013, thanks largely to the targeting of poor neighborhoods by subprime lenders, the median net worth of white families was 13 times that of black families ($142,000 versus $11,000)—up from six times in 2000. African Americans also had twice the unemployment (13.4 percent) and less than 60 percent of the median household income ($34,600). Latinos saw equally devastating declines in family wealth during the aughts.

There are many reasons for the lingering wealth gaps—blacks and Latinos tend to inherit less money and continue to be more susceptible to subprime lending and cuts in wages and employment. But their struggles to make inroads into science, technology, engineering, and math professions play a significant role too. According to the Brookings Institution, 20 percent of American jobs now require specialized technical knowledge. The representation of blacks, Hispanics, and women in most STEM fields is just 40 to 60 percent of what it is in other professions—even as the tech sector grows at triple the rate of the larger economy. In the Bay Area, according to a San Jose Mercury News analysis of census data, the share of Hispanic tech workers actually declined from 5 percent in 2000 to 4 percent in 2010, while the proportion of black tech workers fell from 3 percent to 2 percent.

Silicon Valley’s influx of white and Asian tech talent meanwhile has normalized the $2 million bungalow and driven out longtime residents who can’t afford the nutty rents—in San Francisco, the median one-bedroom apartment now goes for $3,100 a month. Since 2000, the Bay Area’s black population has declined by 6 percent overall, and by 23 and 31 percent, respectively, in the historically black cities of Oakland and East Palo Alto. “No one should be able to squeeze you out of where you live,” Jackson said.

HE SAID THIS not to me, but at a luncheon talk on gentrification at East Palo Alto’s city hall, where, upon arrival, he was immediately beset by admirers who crowded around to greet him. Whether out of graciousness or deft social-media strategy, Jackson endures picture snappers at all of his stops with unflagging charm, but he seemed particularly at ease with this crowd.

East Palo Alto, population 29,000, is a short drive yet worlds apart from the campuses of Facebook and Google. It was originally an unincorporated spillover zone for black Americans barred from buying homes across the tracks in Palo Alto proper. In 1992, it was dubbed the nation’s murder capital. A few years later, it became a ghetto backdrop for the film Dangerous Minds, with Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise” on the soundtrack. Now East Palo Alto is one of the Valley’s last semi-affordable places to live.

“You know, we always measure cities by great events or good things about their location,” Jackson told the audience, which included East Palo Alto’s mayor and City Council members. “There’s a certain importance of Detroit to the automotive industry. We think of Selma, Alabama, we think of the right to vote. In some sense, East Palo Alto is the conscience of Silicon Valley.”

There were mmhmms and chuckles as he continued: “You are the soul of Silicon Valley. You are the frame of reference of Silicon Valley. You are the moral measurement of the values of the fastest-growing industry in the whole world, right here in Silicon Valley. Protect your right to stay here and not be gentrified out of here,” he exhorted. “You have the right to live in East Palo Alto.”

Shifting gears, he urged the crowd to take responsibility for teaching their kids science and math. “Our children”—and here he fell into a call-and-response cadence.

“Can learn.

“Will learn.

“Must learn.”

“This is the laboratory of hope and new possibilities,” Jackson went on, as audience members shouted affirmations. “And we must make that real in our lives.”

After the speech and a short Q&A session, someone passed a microphone to David Chatman, a big man who had worked at Home Depot before attending StreetCode Academy, a community-based hacker school. He later landed an internship at Inflection, a data company in Redwood City. “Thank you for making my 24th birthday something crazy,” he told Jackson, wiping away a tear. “I grew up listening to you from my father, my mother, my grandparents.”

“I guess that makes me an old man, don’t it?” Jackson responded. He shook Chatman’s hand, and kept holding it as he led the crowd in “Happy Birthday.”

JACKSON HASN’T been shy about using tech companies’ own tools to push back at them. Take Twitter, which, like many tech companies, has a workforce far less diverse than its user base. Twitter is particularly popular among African Americans—27 percent of black internet users have Twitter accounts, compared with 21 percent of whites. But it resisted releasing its diversity stats even after some of its peers had relented, so Jackson decided to apply the heat.

Rainbow PUSH teamed up with the online activist group Color of Change, which encouraged its million members to tweet at Twitter’s corporate account and ask the company to cough up the data. A week later, Twitter caved. It turned out that just 1 percent of its tech workers were black (same as Facebook), and only 10 percent were women, compared with 15 percent at Facebook and 17 percent at Google. “Like our peers, we have a lot of work to do,” acknowledged Twitter diversity chief Janet Van Huysse.

By December, Jackson had helped persuade two dozen companies, including Facebook, Pandora, and Amazon, to release their stats. But admitting to a problem is only the first step toward doing something about it, and Intel, which had been quietly releasing its own diversity data for years, was ripe for a more transformative move. It was also in need of a PR boost; the company had just taken a lot of flak for pulling ads from the gaming news site Gamasutra after it ran a column critical of misogyny in the gamer community. (Intel promptly apologized and reinstated the ads.)

Following up on earlier conversations, Intel’s diversity chief Hudnell got in touch with Wing, Jackson’s program director, to discuss Intel’s efforts. In early December, Rainbow PUSH hosted a diversity conference on the Intel campus, and invited other companies to take part. The next day, CEO Krzanich invited Jackson to join him for the unveiling of the company’s new diversity initiative at the International Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. Intel pledged that its workforce would, by 2020, match the diversity of the existing talent pool for any given job; for some technical positions, it would mean increasing the representation of non-Asian minorities or women by as much as 48 percent.

The timing of Jackson’s diversity push in the Valley “really helped,” Hudnell told me, although the move was in the company’s interest. Krzanich had decided that Intel needed a more diverse workforce after watching a team of male engineers struggle to create a smartwatch for women. “You’re always going to pay an opportunity cost by not having certain creative life experiences in the room,” Hudnell said. “And race and gender play deeply into your life experiences.”

AFTER THE EAST PALO ALTO shindig, I shuttled Jackson over to the fastidiously landscaped campus of Stanford University, where he was scheduled to give a pair of talks. “This is such a wonderful place to sit,” he said as we rested for a moment on a bench under a large oak tree. Talk turned to his nephew, who’d graduated from Stanford with a degree in mechanical engineering. “He’s teaching at MIT,” Jackson scoffed. “He had no job offers in Silicon Valley.”

“Do you think there was any discrimination there?” I asked as we followed a meandering trail toward the Black Community Services Center, his first destination.

Jackson stopped in his tracks. “Look here,” he said. “You do business with people that you know, trust, and like. If you are not in the circle, not trusted, not liked, and then stereotyped, you can’t get in. Unless you have an external force that breaks the rhythm of that.”

Later, after a standing-room-only speech at Tresidder Memorial Union, we headed to a small theater in San Francisco’s affluent Laurel Heights neighborhood for a screening of the movie Selma. Back in 1965, after Bloody Sunday, Jackson went to Selma to participate in the march to Montgomery; MLK Jr. was sufficiently impressed with his leadership skills that he set aside concerns in the movement over Jackson’s showboating tendencies and put him in charge of the Chicago chapter of Operation Breadbasket. But in the postscreening discussion, Jackson wasn’t in the mood to reminisce. “There is a fear I have of getting all emotional about it and looking in the rearview mirror—and not looking out the windshield,” he said. He plunged into his stats about the lack of minorities on Silicon Valley boards, and the need to educate black and Latino kids in science and math. He spoke of the distinction King drew between the movement’s “freedom allies” and its “equality allies,” and professed to be “at least as upset about Silicon Valley as I am about Alabama.”

“You might can’t get to Selma, but you can get to East Palo Alto,” he said with a mischievous smile. “I wish I had a witness. Say amen, somebody!”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.