02 Aug The other pipeline:The tech industry in an era of mass incarceration by Megan Rose Dickey

In 2012, California voters approved Proposition 36, which led to the amendment of the three strikes provision of the 1994 crime bill. Two main changes made to the law were that the third strike needed to be a serious or violent felony and that those currently serving a third-strike sentence could petition the court for reduction of their term to a second-strike sentence — if they would have been eligible for second-strike sentencing under the new law.

For Leal, that meant that he could meet with a judge for potential re-sentence. In 2013, Leal met with the same judge who originally sentenced him to 25 years to life. The judge re-sentenced Leal to seven years and a week later, Leal was released from prison.

“That was probably the best feeling I’ve ever felt,” Leal tells me. “It’s amazing. It’s one thing to be in prison, but to be in prison with a life sentence — I can’t even begin to explain how tough that is because you could literally die in prison. Who the hell wants to die in prison? There was the uncertainty of not knowing when you’re going to get out, which was really hard, so when I did walk out of there, it was probably one of the best moments of my life.”

While at The Last Mile inside San Quentin, Leal met RocketSpace CEO Duncan Logan, a friend of Redlitz’s, who says he had never been to a correctional facility before. RocketSpace is a co-working accelerator that has housed startups like Uber, Spotify and Leap Motion.

“I actually went in before the demo day to do some coaching,” Logan tells me. “That was when it kind of struck me. It just shattered all of my illusions of what I thought I would see or experience.” He tells me he sees the criminal justice system in a different way. Before, he was in the bucket of “if we remove [criminals], it’ll be a better place,” he tells me. “I was in a fairly common misunderstanding of what was going on with crime. Certainly in a total misunderstanding of what a correctional system is and what it could be — I think I’ve gone through a total transition on that.”

When demo day came around, Logan returned to San Quentin and was impressed by Leal’s presentation. Logan told Leal that if he ever got out, he would hire him. He kept his word. Of Leal, Logan says: “He’s achieving more than most of the staff sitting here.”

Leal joined RocketSpace in 2013, a year after he was released from San Quentin. Since then, he’s gone from moving furniture at RocketSpace to setting up IT equipment and doing some programming as RocketSpace’s manager of campus services. In transitioning from prison to the tech industry, Leal has seen a number of parallels.

It’s one thing to be in prison, but to be in prison with a life sentence — I can’t even begin to explain how tough that is because you could literally die in prison.

— Chrisfino Kenyatta Leal

“One of the things that I noticed immediately about RocketSpace and this whole tech hub at RocketSpace is there’s a lot of energy there,” Leal says. “In prison there’s a lot of energy. The big difference is that so much of the energy in prison is chaotic. Inside RocketSpace, everything is focused on these goals and trying to get this product to market, raise money, be successful.

“So I think that inside prisons there’s this attitude of just making the most of whatever you have to work with. In prison, it’s all about the minimal viable product. There’s a parallel there as well. I think that one of the biggest parallels I’ve found about the entrepreneurship and tech world is that failure isn’t a bad thing. Failure is actually a good thing. You can learn things from failure.”

People in the tech industry have made some steps toward creating opportunities for those who have gone through the criminal justice system. It’s time to focus on what happens before people enter the criminal justice system.

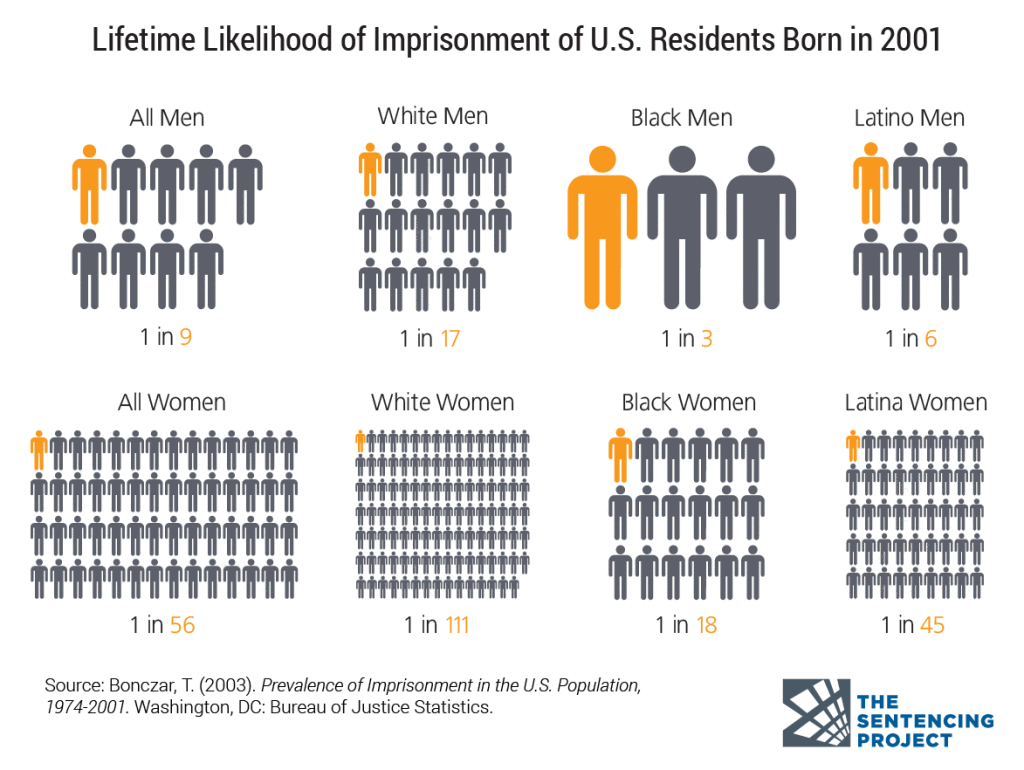

In total, black people are more likely than white people in America to be arrested and, once arrested, blacks are more likely to be convicted, according to The Sentencing Project. And once convicted, blacks are more likely than whites to face harsh sentences.

Technology and data could play a big role in dismantling the system that leads to a disproportionate number of black men ending up in prison.

According to the ACLU’s Zamora, there is a lack of uniform data collection on the various phases of the criminal justice system.

“Everything from when people are stopped to all the way through a trial, as well as how decisions are made throughout the process and how those decisions are affecting different communities,” Zamora says. “So, there’s a big data void in criminal justice.”

With the help of technology, there could be a lot more transparency to the criminal justice system simply by surfacing the data the government does have.

Right now, a lot of people feel like there’s a bit of a black box around what’s going on in local police forces and in the system at large, Justin Erlich, special assistant attorney general, in the office of Attorney General Kamala Harris, tells me. That’s because, Erlich says, a lot of the tech and infrastructure that criminal justice agencies use are pretty old.

“It’s not necessarily that people are trying to hide or not share the data as much as it’s actually amazingly difficult, manually, to get out and extract data,” Erlich says. “I think that making sure we are all working together to get modern technology into all of these agencies is critical for us to really then be able to use APIs or extractions of the cloud to analyze and research what is going on.”

Erlich led the team that recently relaunched OpenJustice, an effort by the California Department of Justice to make law enforcement data more transparent. But in order to make serious strides, and move toward real-time criminal justice data reporting and better policies, Erlich says, we’ll need more public-private partnerships between the government and leading tech companies.

Getting more technology and the tech industry involved in criminal justice efforts pays dividends.

— Justin Erlich, special assistant attorney general, office of AG Kamala Harris

So far, Erlich says there has been some high-level support from companies like Facebook, for example, but a lot more support is needed.

Technology could also be helpful with better understanding how to reduce the number of those entering the criminal justice system through pre-trial and bail reform.

“Instead of locking people up, we can use technology to better keep track of folks, so they don’t have to enter the system in the first place,” Erlich says. “And on the backend, we can start training folks that will help diversify the technology pool. That’s not just simply from a demographic perspective but also from a worldview perspective. I think it’s important that a lot of people who end up touching the system are then put in places where they can take action to reform it.”

Not everybody goes through the criminal justice system, so there’s a lot of value in sharing that perspective with others, Erlich says.

“Getting more technology and the tech industry involved in criminal justice efforts pays dividends both for society itself but also directly to the tech industry,” Erlich says.

Meanwhile, the White House recently challenged artificial intelligence experts to help reform the criminal justice system. Speaking at a Computing Community Consortium workshop, Lynn Overmann, head of the White House Police Data Initiative, said AI and data analytics could be useful in improving questions on parole screenings, analyzing police body camera footage and in analyzing criminal justice data. Oakland, California, for example, has seen a drop in the use of force by both police and citizens since deploying body cameras.

That said, inserting technology into the criminal justice system doesn’t necessarily mean good will come from it. In certain states throughout the country, courts are using algorithmic software to predict the likelihood of someone committing a crime in the future. In analyzing risk scores from Broward Country, Florida, for instance, the investigative team at ProPublica found that the software used in the sentencing process is biased against blacks. However, the private company behind the software could work to overcome this bias if they decided to implement updates.

By reforming the criminal justice system, there’s also an opportunity to fill the so-called labor shortage in the tech industry. Through programs like The Last Mile and other proactive approaches to teaching tech skills to former prisoners, the tech industry could gain access to untapped talent while also tackling diversity.

“Unfortunately, we know we’ve sort of got two distinct diversity issues,” Erlich says. “One is in the tech sector. We don’t have the diverse labor set that we would hope for many reasons. Similarly, unfortunately, also again for many societal reasons, those who are entering the criminal justice system are not diverse in a different way, which is, they’re disproportionately minority and African-American and I think both of those results are an example of broader societal issues that we’re struggling with.

And they are sort of an opportunity for us to really focus on addressing both of those, which is how can we use technology better to understand how to reduce those entering the system.”

Addressing the problems of inequity and racial justice in the criminal justice system would allow for more opportunities for communities of color to thrive in many different ways.

”The criminal justice system really embodies a lot of our problems with race in our country,” Zamora says. “So if we can fix that, I do think we’ll see a lot of positive changes.”

SOURCE

Featured image by Bryce Durbin / photos by Yashad Kulkarni

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.